A front-loaded rally as gains peter out

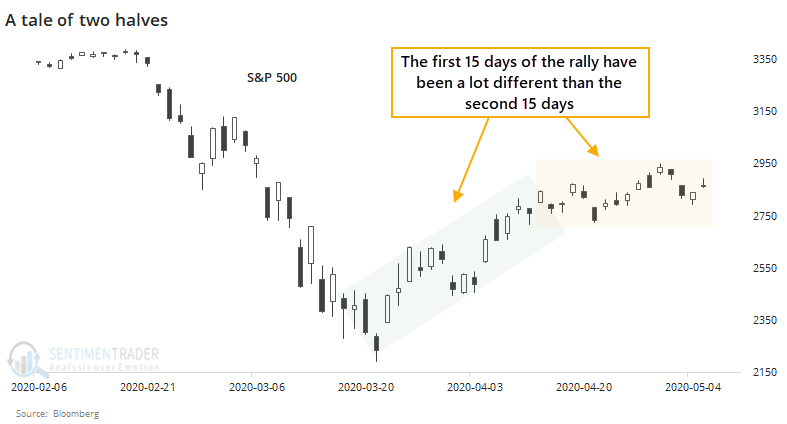

Since stocks bottomed on March 23, they've shown impressive gains. After 30 days, the S&P 500 was still showing a gain of nearly 30% from its lows.

The trouble (maybe) is that that the rally has been so front-loaded. The first 15 days of the 30-day rally generated virtually all of the gains. While the second 15 days have shown a gain, it was barely positive.

No matter what markets do, there are always boo-birds suggesting that things will fall apart. They're using this first-half, back-half argument now to spin the idea that buyers have run out of juice and we're about to roll over.

So, let's check.

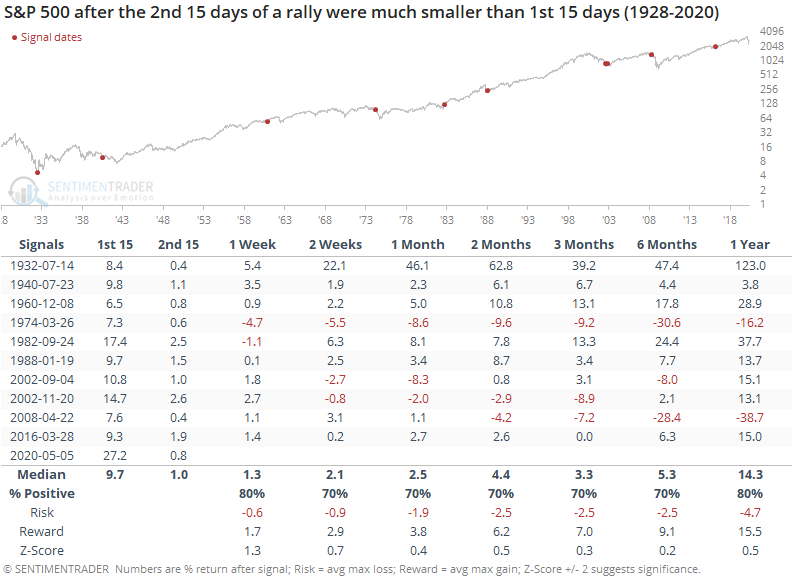

We'll go back to 1928 and look for every time the S&P 500 set a 52-week low, then rallied for 30 days. The gain during the first 15 days of the rally must be at least 3 times greater than the gain during the second 15 days.

Returns were okay most of the time, but there were two big losers over the next 6-12 months. If the S&P fell back and showed a loss or only a small gain over the next month or so, then that weakness tended to bleed over into longer-term returns as well. Part of that makes sense because the one-year returns include returns during the first month, but there was a long-term difference between the rallies that saw renewed buying interest over the next month and those that didn't.

Now let's look at those 30-day rallies off a low when the second 15 days were more comparable to the first 15 days.

It's rare to see bigger gains in the second half of a 30-day rally than the first half. And even when we did, it didn't really matter, at least across most time frames.

Over the next two months, the rallies with a weak back half tended to do quite a bit better than the rallies with a more robust second half. The biggest difference was a year later when the rallies with a strong second 15 days averaged nearly 22% and had only a single loss (though that loss was large, from 2001).

Overall, there isn't anything in the pattern to suggest an investor should become more defensive just because the gains have petered out. The biggest caveat would be that if we do roll over from here and show losses over the next 1-2 months, it would usher in some of the more unpleasant longer-term precedents.