Despite gains, more consumers expect stocks to fall

We've been seeing for months that consumers haven't really been buying into the idea of an immediate economic recovery. And when stocks were gyrating wildly, they were hesitant to believe in the idea of a sustained rally.

Four months later and more than 25% higher in many indexes, consumers still aren't buying it.

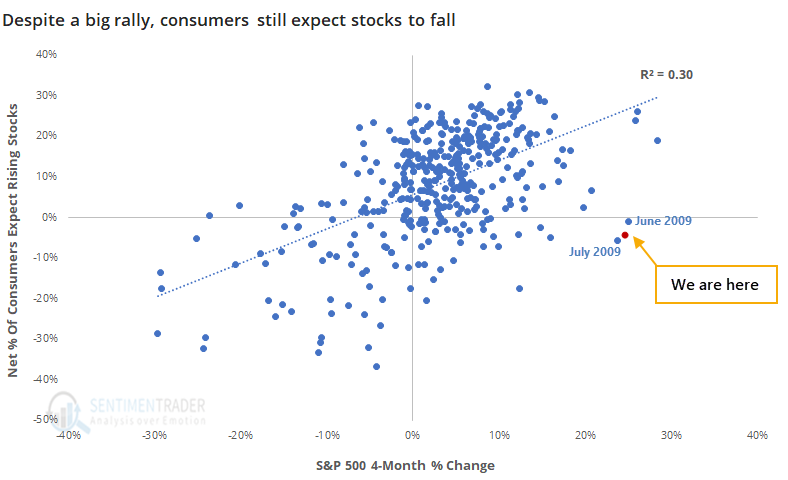

The latest survey from the Conference Board shows that more consumers expect stock prices to decrease over the coming months than increase. This is highly unusual - there is a strong positive relationship between the S&P 500's rate of change over the past four months and the net percentage of consumers who expect stocks to rise going forward.

Recency bias is a real thing. The only other months in more than 30 years of history when the S&P gained more than 20% and yet consumers, on balance, expected stocks to fall were June and July 2009.

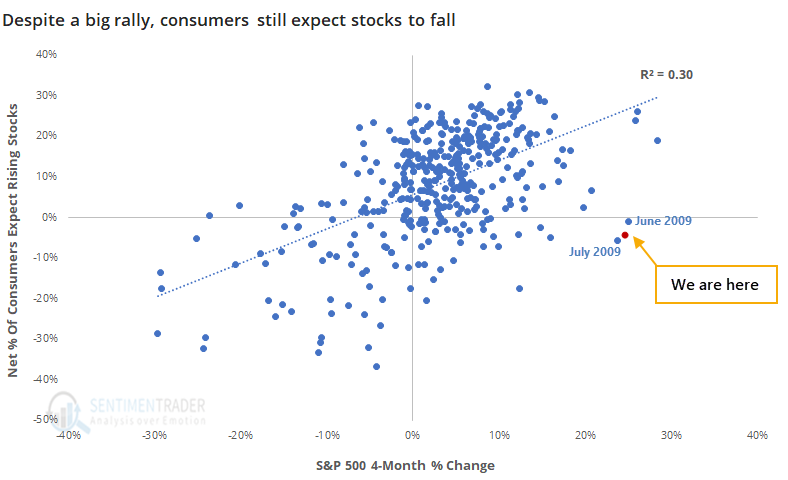

Below, we can see that the S&P's annualized return when consumers were pessimistic on stocks was very impressive. Even though this was the case during much of 2008, most of the other months showed a strong contrary bias.

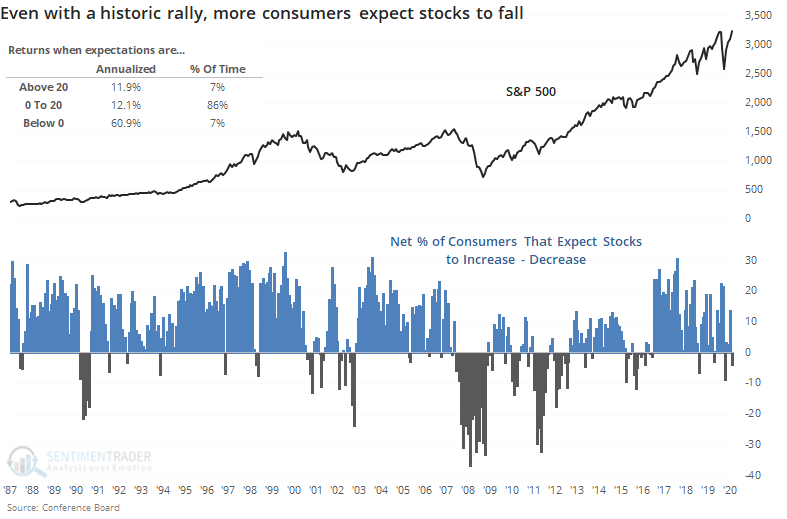

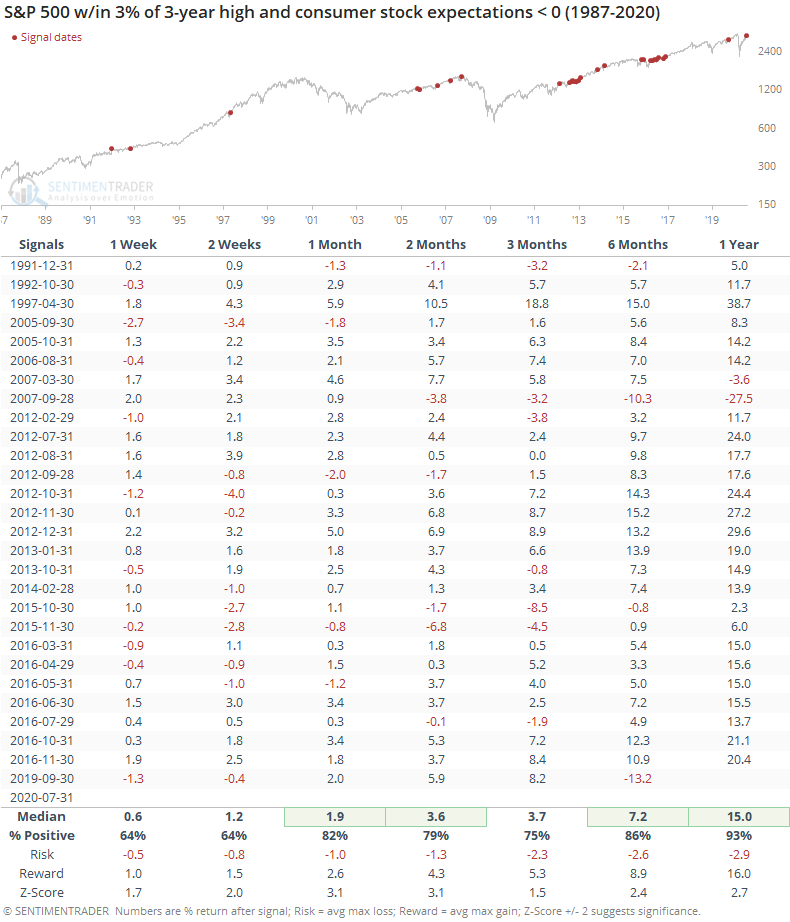

When the S&P finished a month within 3% of a multi-year high, and yet fewer consumers expected stocks to increase than decrease, it was a good medium- to long-term sign for stocks.

Like fund flows and a few other surveys, this data does not at all support the idea that investors are excessively optimistic. But more indicators show that they are, enough so that Dumb Money Confidence has hovered at or above 80%.

There is no good way to reconcile them all - there are rarely any times when every indicator agrees. It's just a matter of determining what matters most and using weight of the evidence. In recent weeks, that has tilted more toward the idea that risk is high over a multi-week to multi-month time frame, but is skewed more toward the upside over a 3-12 month time frame.