What negative interest rates might mean for stocks and the dollar

Despite the big recovery in stocks and bonds, many are still doubting the long-term economic outlook in the U.S. That has raised the possibility of negative interest rates, something previously considered inconceivable.

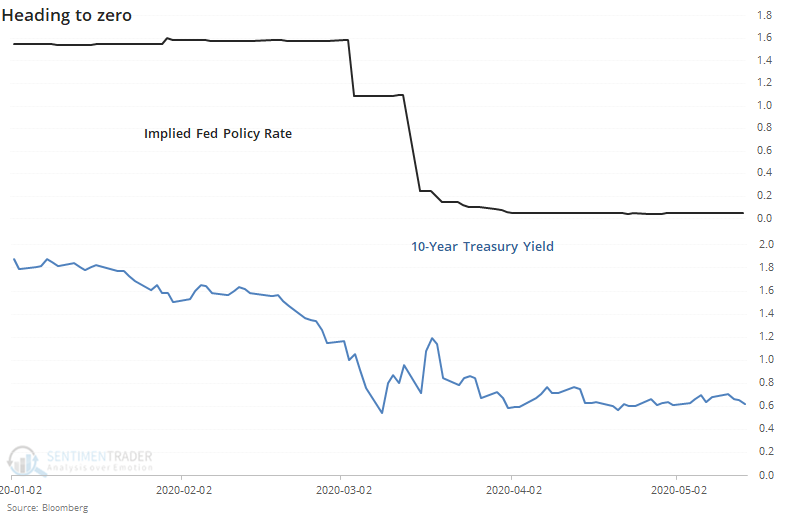

Markets are already pricing in the potential, with various Fed Funds futures contracts flirting with below-zero yields. The primary market-based rate of longer-term expectations, the 10-year yield, is hovering near all-time lows but remains above zero for now.

The prospect is not out of the question, and it's getting increasing attention in the media.

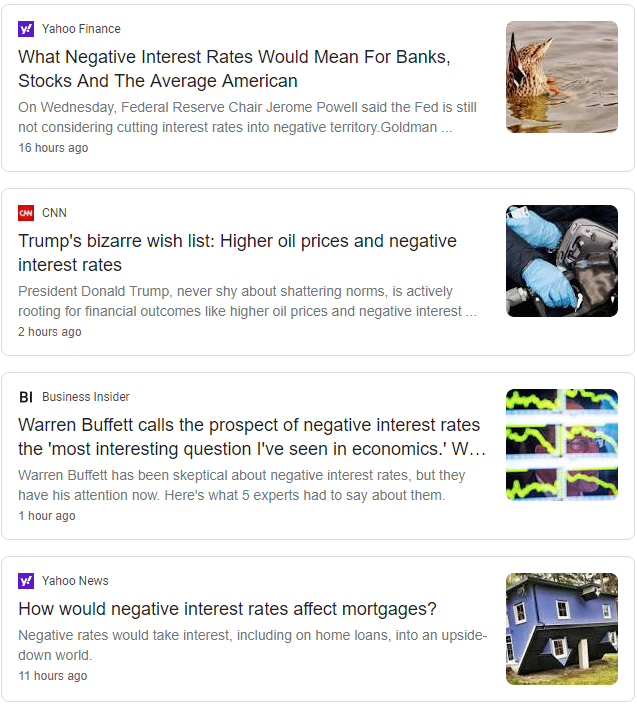

The U.S. wouldn't be the first or only member of the zero-rate club; several countries have already experienced it. This gets a little tricky depending on what we mean by "interest rate" because not all countries operate in the same way. So, we'll go with the yield on sovereign 10-year notes, as it shows market-based long-term expectations of economic growth better than central bank policies might.

Interestingly, when rates first went negative (or did so after a prolonged stretch back above zero), the major stock indexes in those countries didn't seem to suffer much, at least in U.S. dollar terms.

In the month following inverted interest rates, the stock indexes rallied every time, with impressive gains. Even over the next 3-6 months, there was only a single loss, though it was a large one after stocks in Denmark suffered a failed rally in 2016.

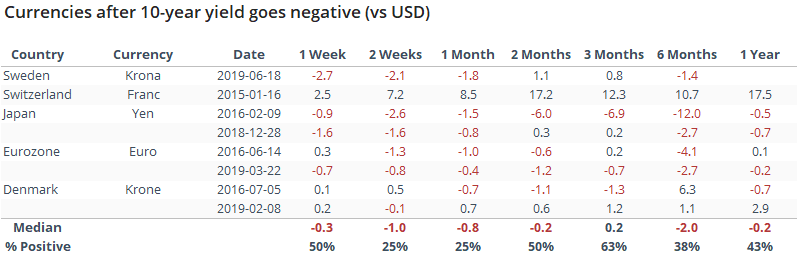

Their currencies were another matter.

These all use the U.S. dollar as the cross-currency, so maybe it's just a reflection of overall strength in the buck. Still, there was a pattern of weakness with the only real exception being the Swiss Franc in early 2015.

While it's easy to succumb to stories of destruction when markets do unprecedented things, it's not always a negative. Most of the time, it's not. That includes those times of severe tumult that make investors willing to pay governments to borrow money.