Two sides of the S&P 500 - total return vs. equal weight

We've seen how a few stocks have been taking over the market (here and here) which has masked some underlying weakness (here and here). While the Advance/Decline Line has broken out to a new high, that doesn't mean the gains are evenly spread, not even remotely. The stocks-only A/D Line still remains below its prior high.

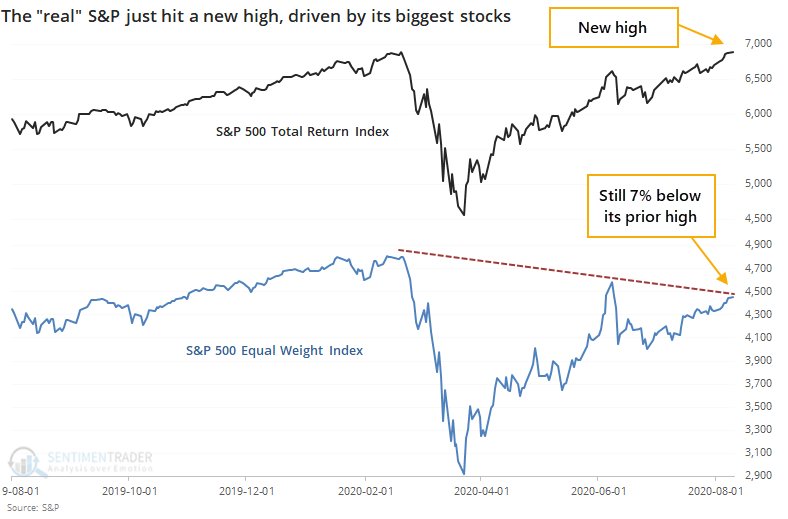

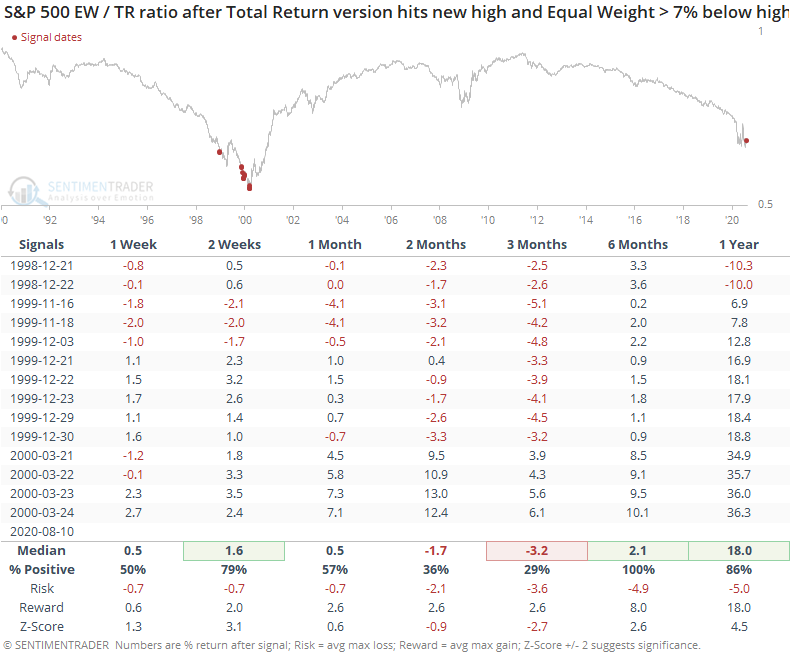

These quirks have allowed the S&P 500's Total Return index to close at a new all-time high. This is the version of the index that takes dividends into account, which is what a "real" investor would receive. Yet the Equal Weight version of the index, which puts all 500+ stocks on equal footing, is still more than 7% below its own high, even though its relative performance has picked up in recent days.

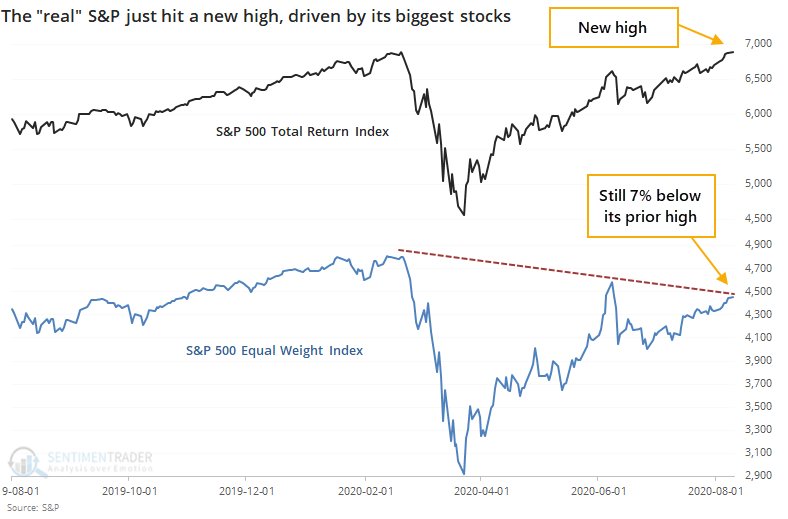

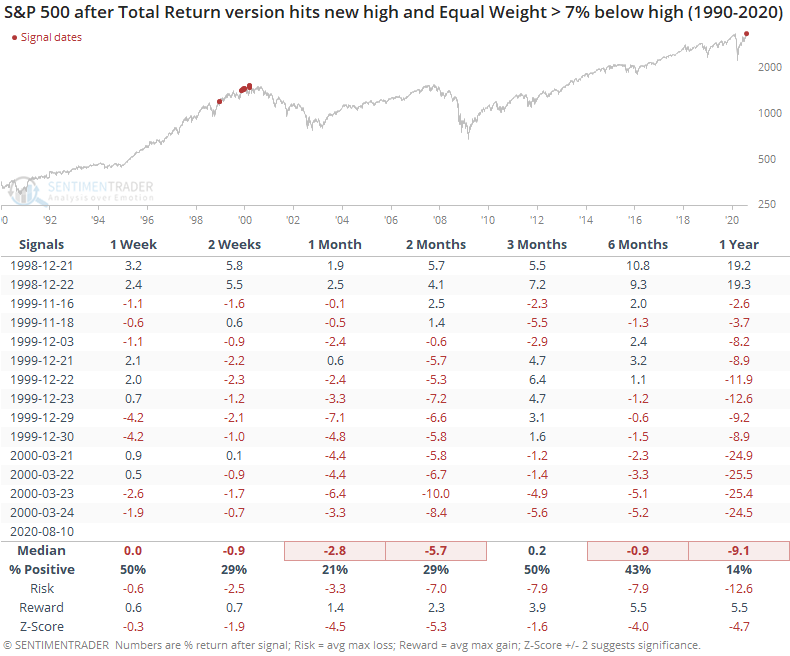

Over the past 30 years, there have only been four other days when this kind of quirk triggered - two days in late December 1999, and two in mid-March 2000. Even when relaxing the parameters to look for a 5% divergence, only a handful more days showed up, mostly around the same time frames.

In late 1998, the S&P still managed to show some gains going forward, but the others were disastrous. The Total Return version of the index showed only slightly better returns since dividends weren't much of a factor around that time.

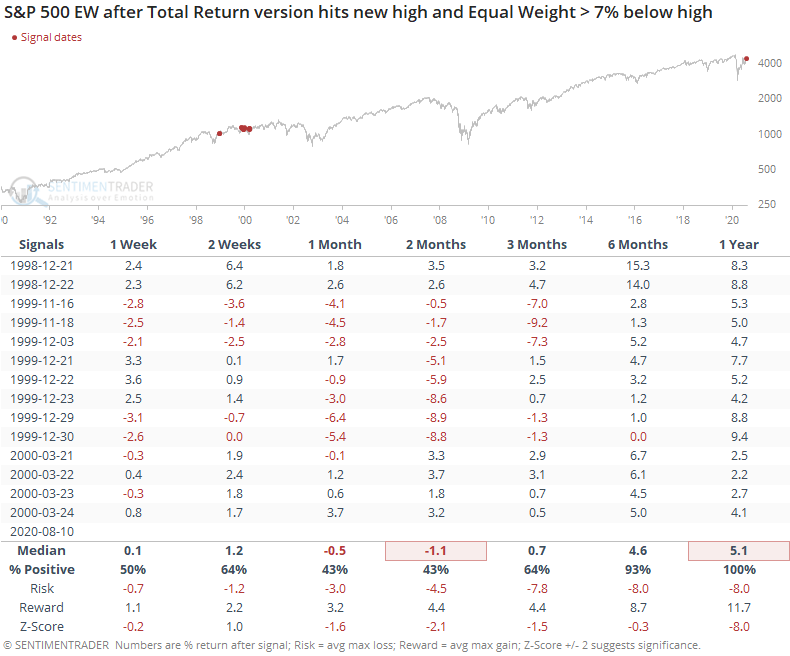

The Equal Weight version of the S&P held up much better.

If we look at the ratio of the Equal Weight to Total Return versions of the S&P, it clearly favored the former over the next six months.

With the attention focused on the handful of dramatic winners in recent months, and investors extrapolating those wins far into the future, the risk is high that those extrapolations won't come to fruition. Whether due to competition, new regulations, or simple gravity, the U.S. economy is not set up to reward a near-monopoly for long. Those investors relying on the capitalization-weighted version of the index are at the mercy of that history being rewritten now.